Jan Hřebejk – director

Honeymoon should thematically conclude the loose trilogy of Kawasaki’s Rose – Innocence – Honeymoon, which as its central theme combines the motif of a secret in the past which can have an unexpected impact upon the present. Do you regard Honeymoon as such a conclusion of this trilogy?

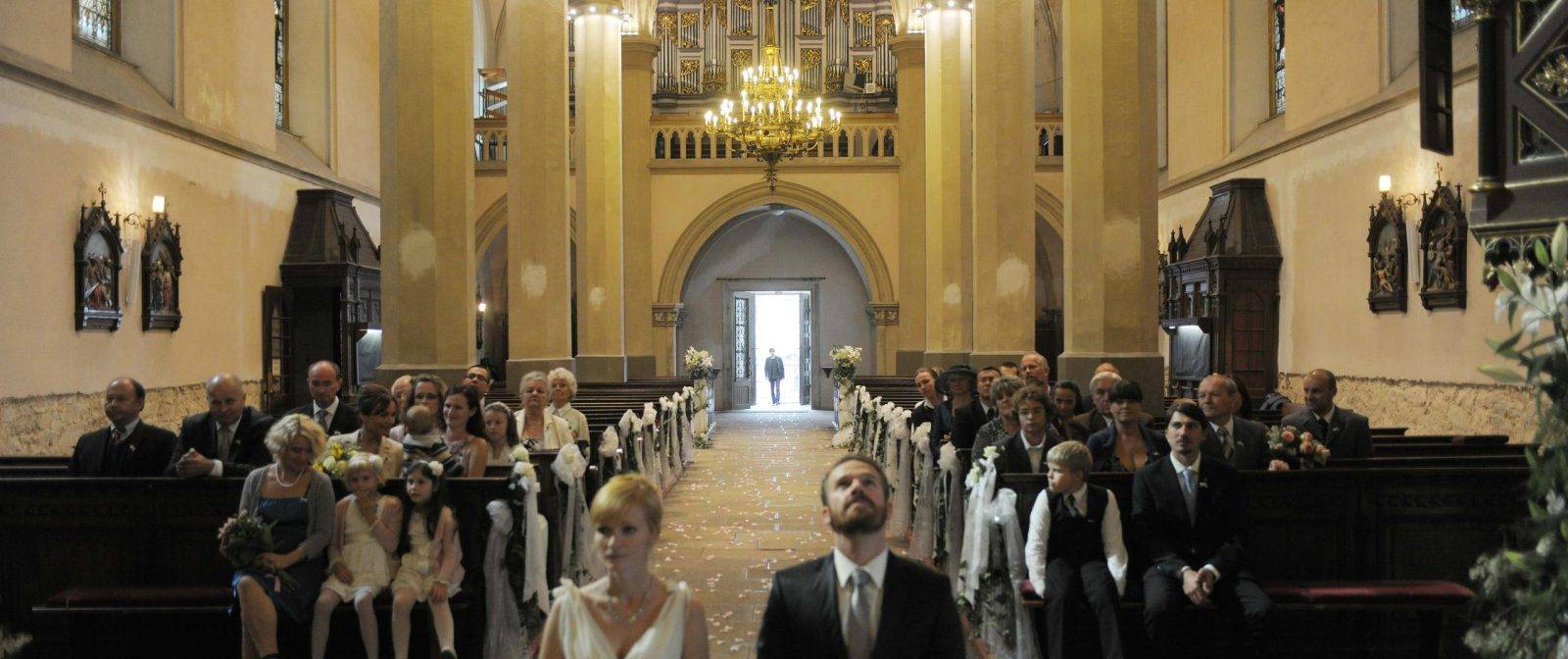

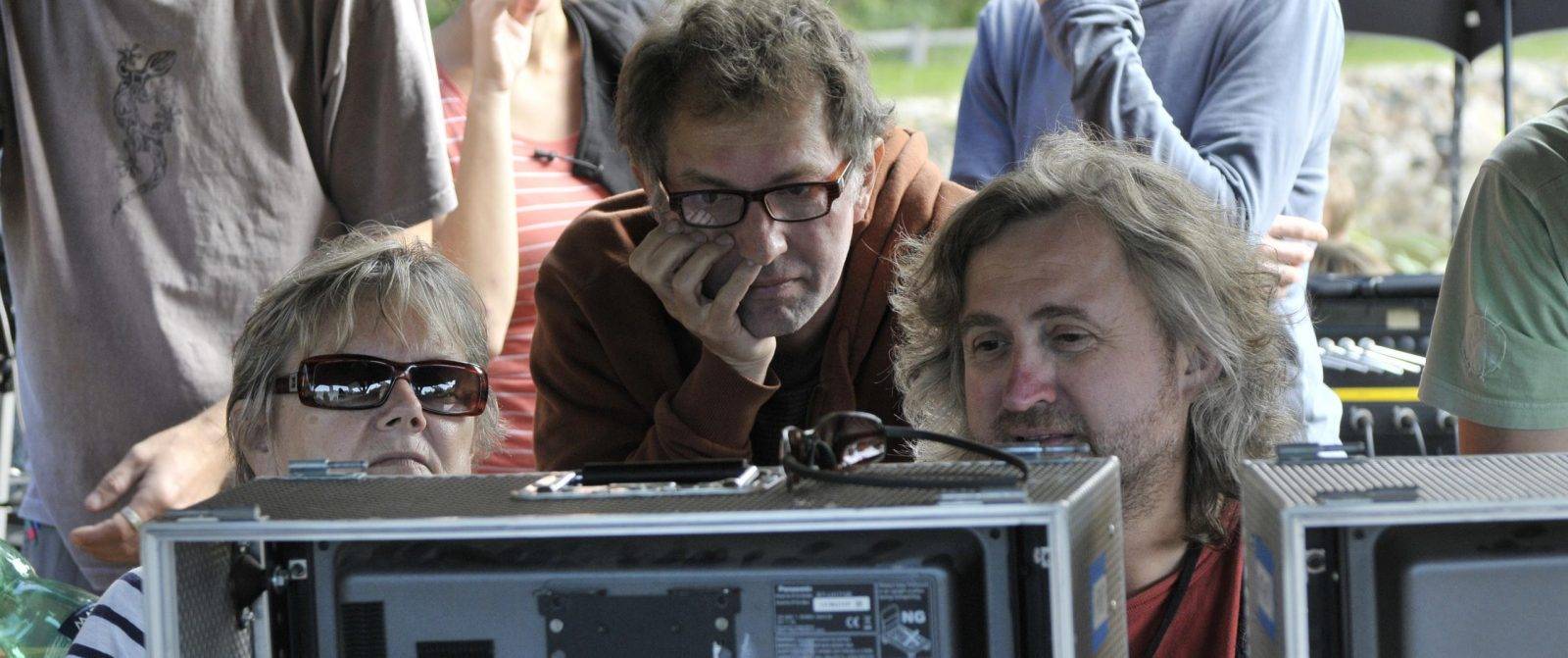

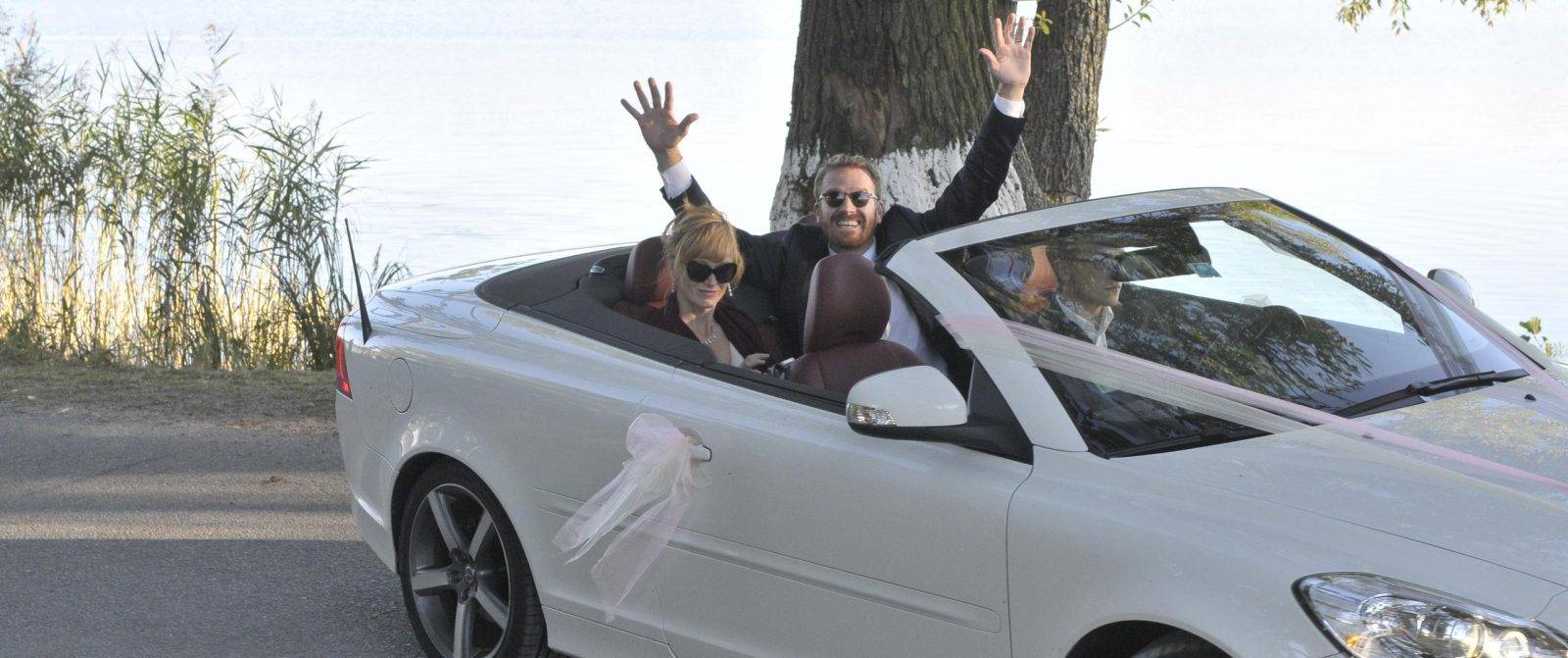

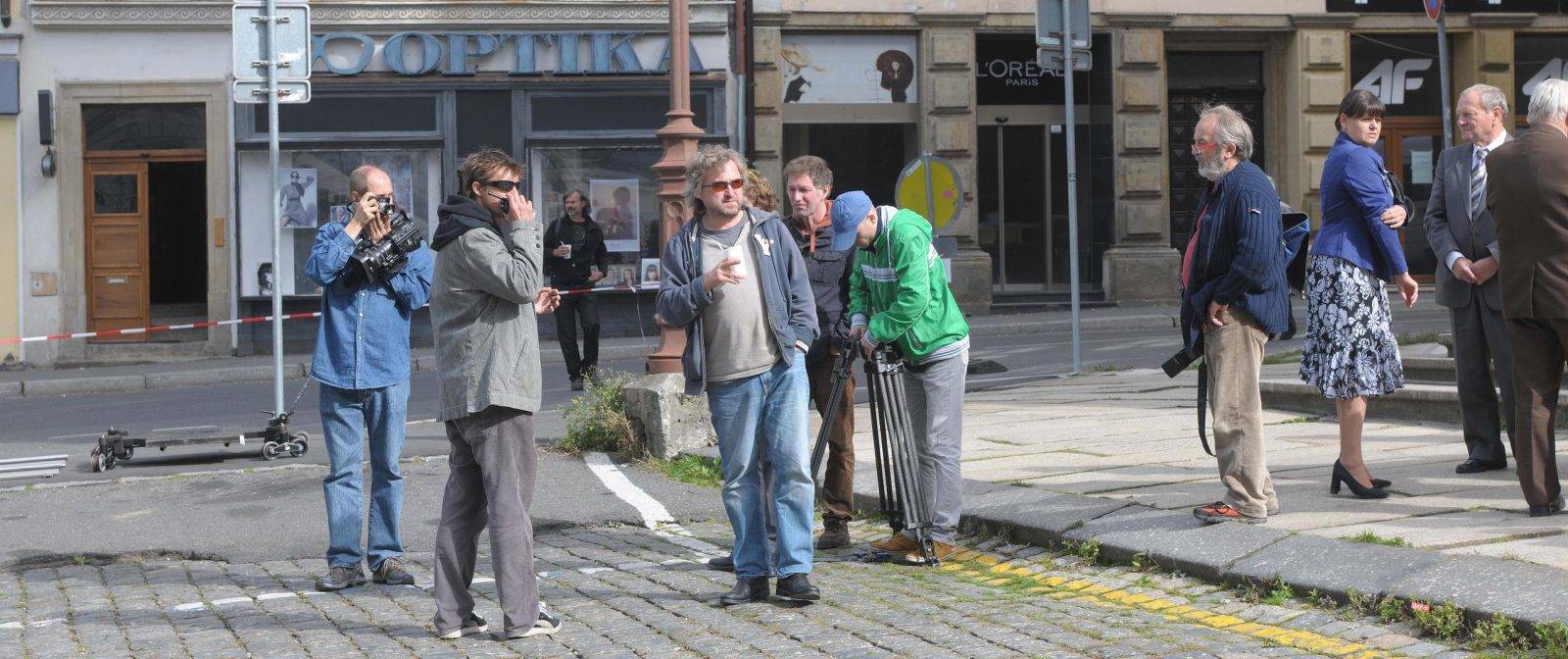

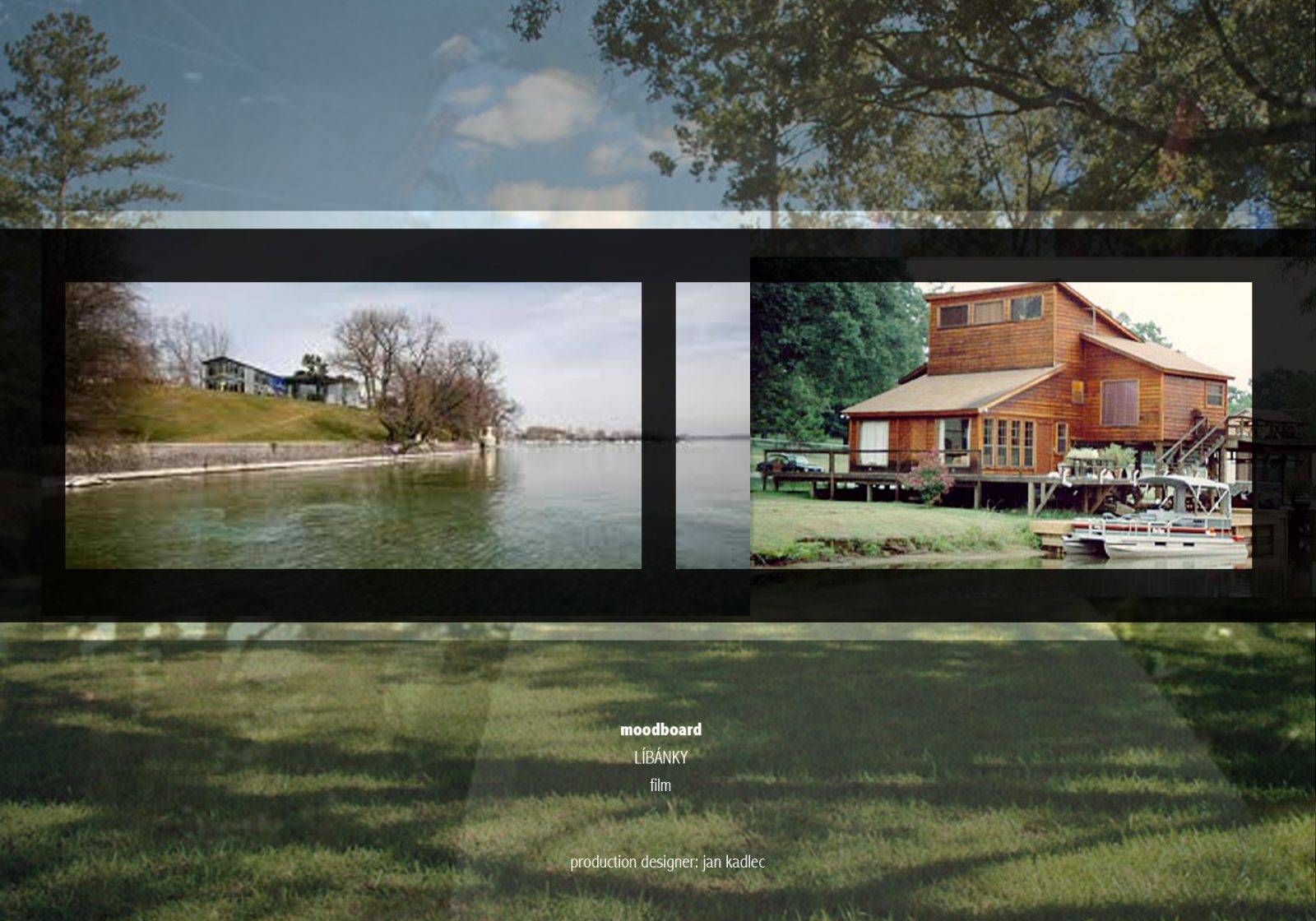

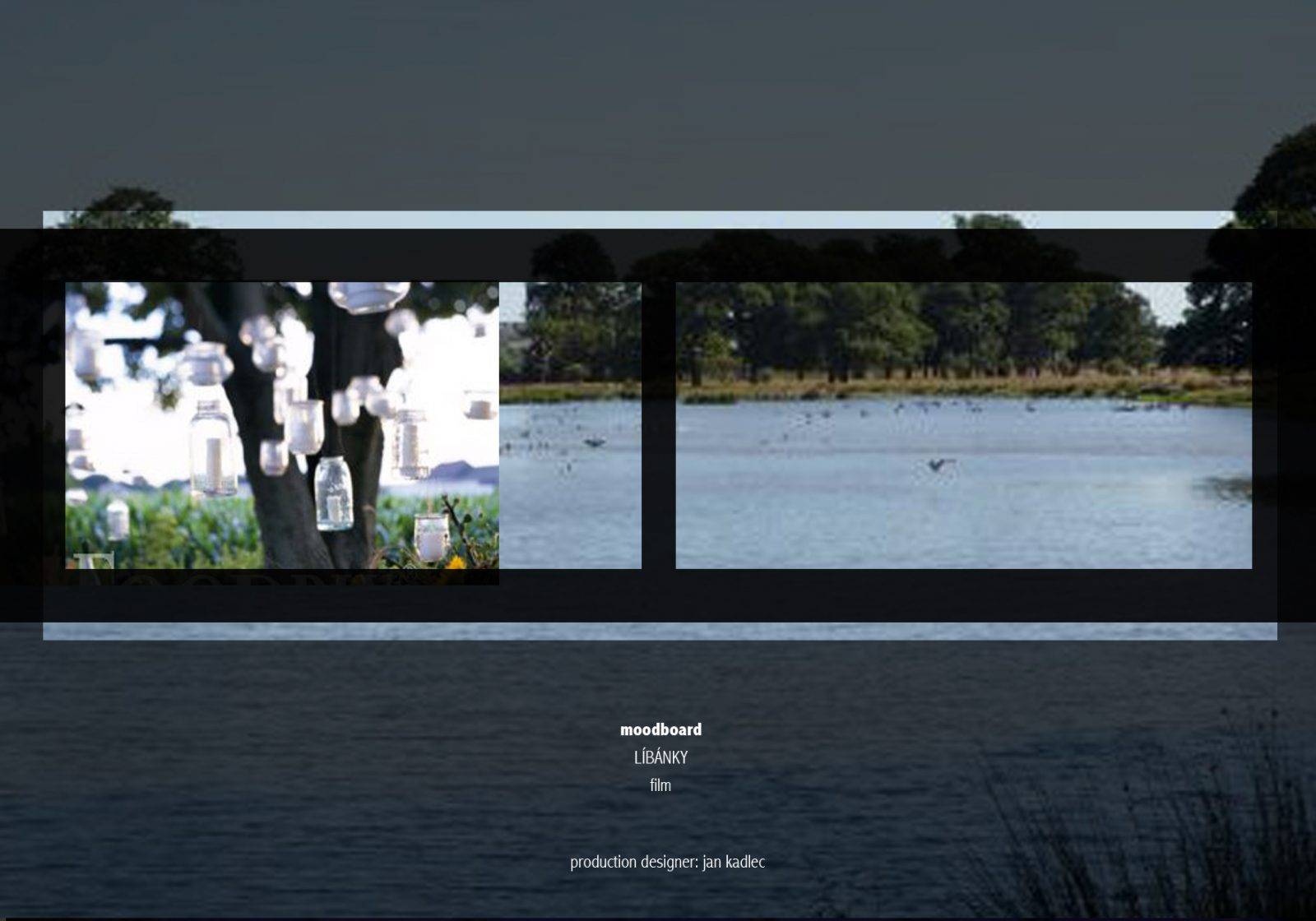

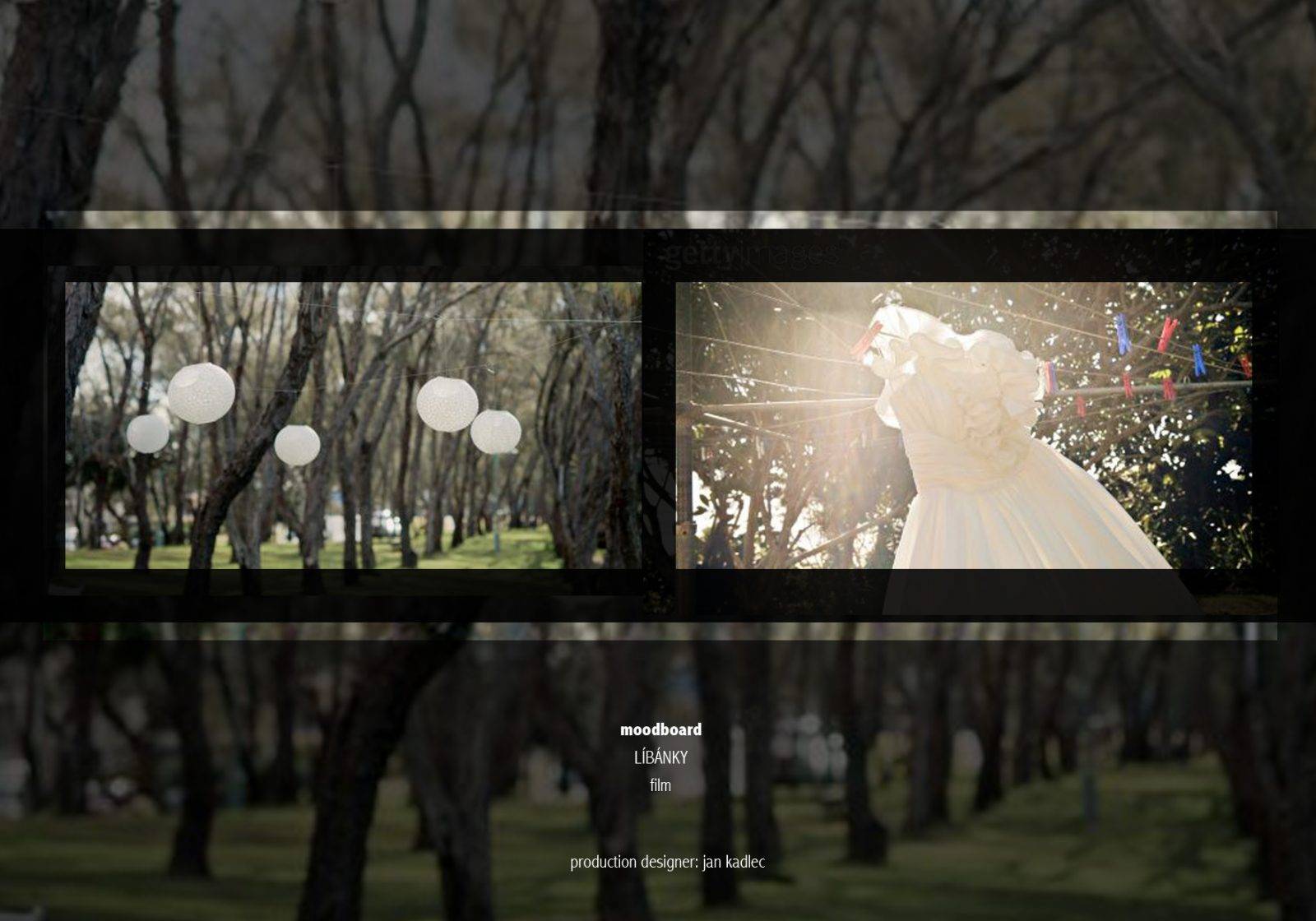

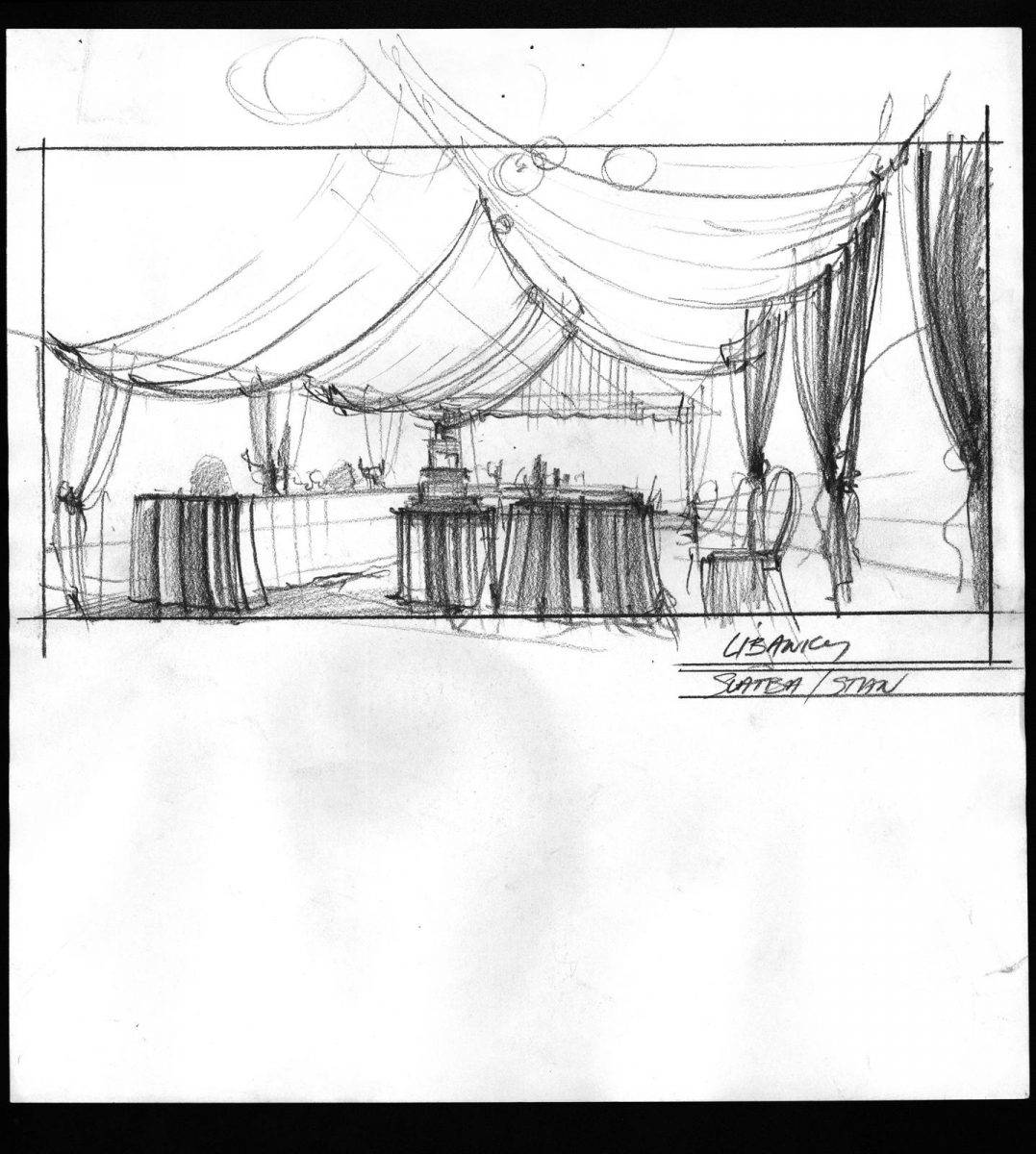

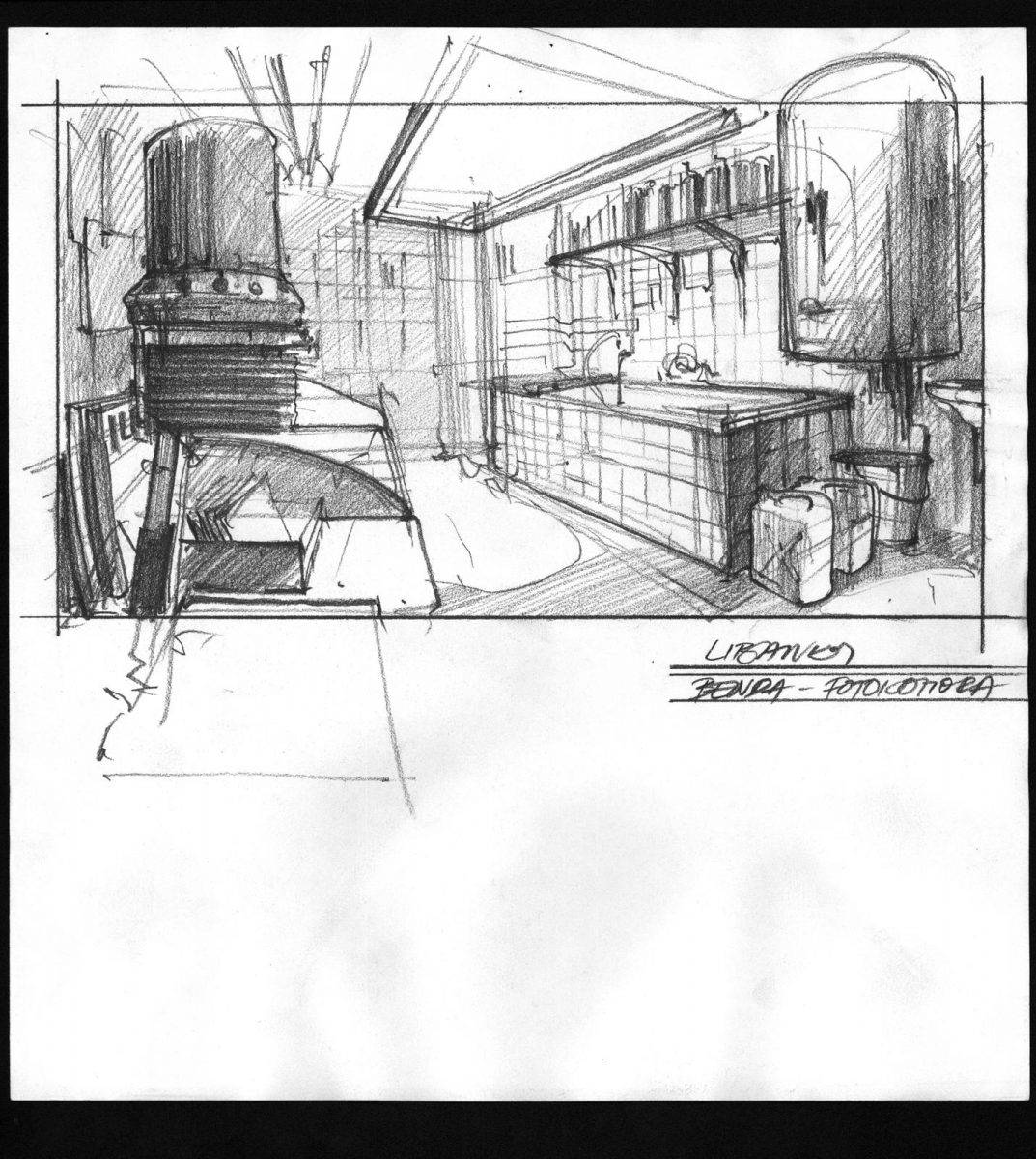

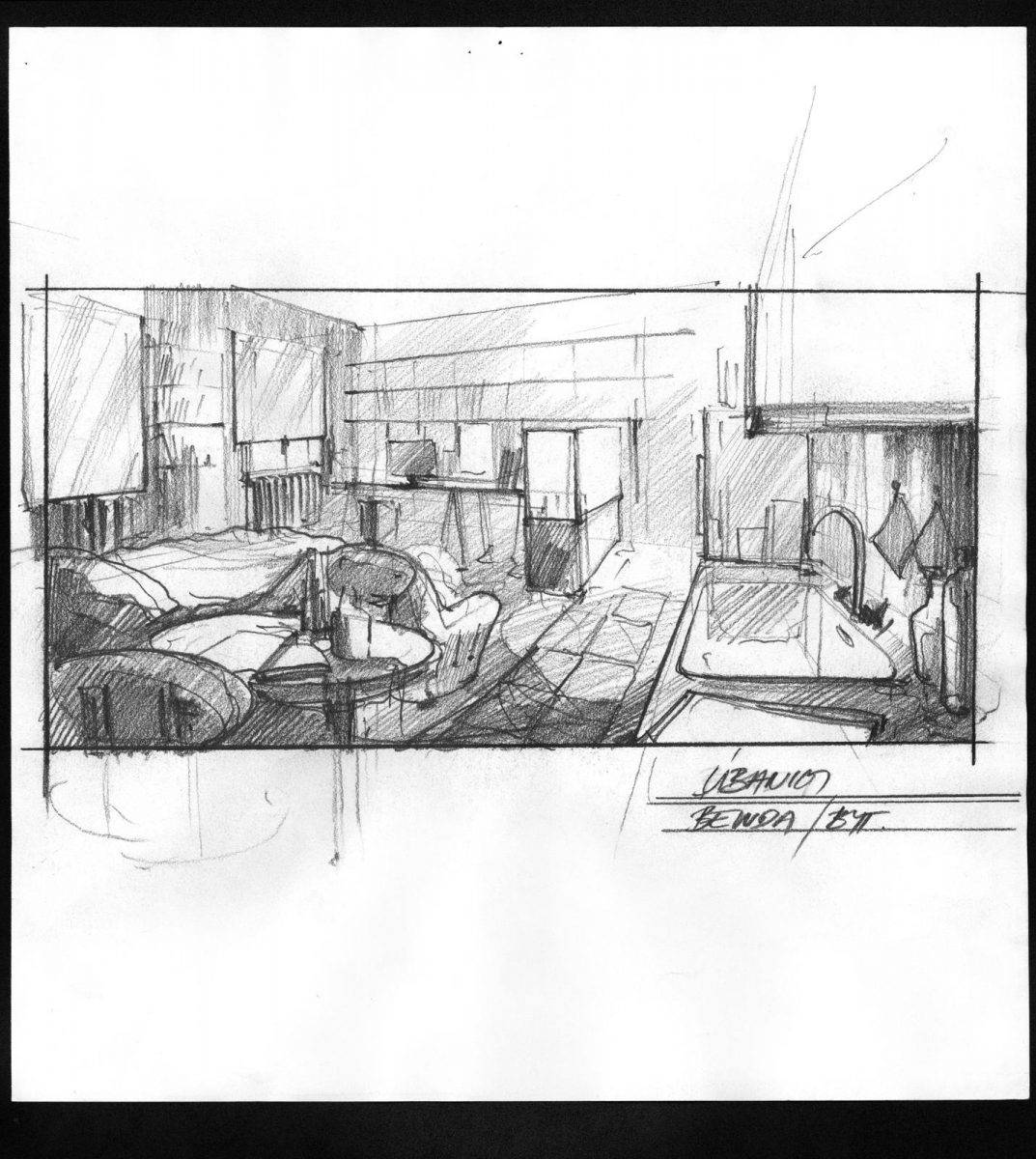

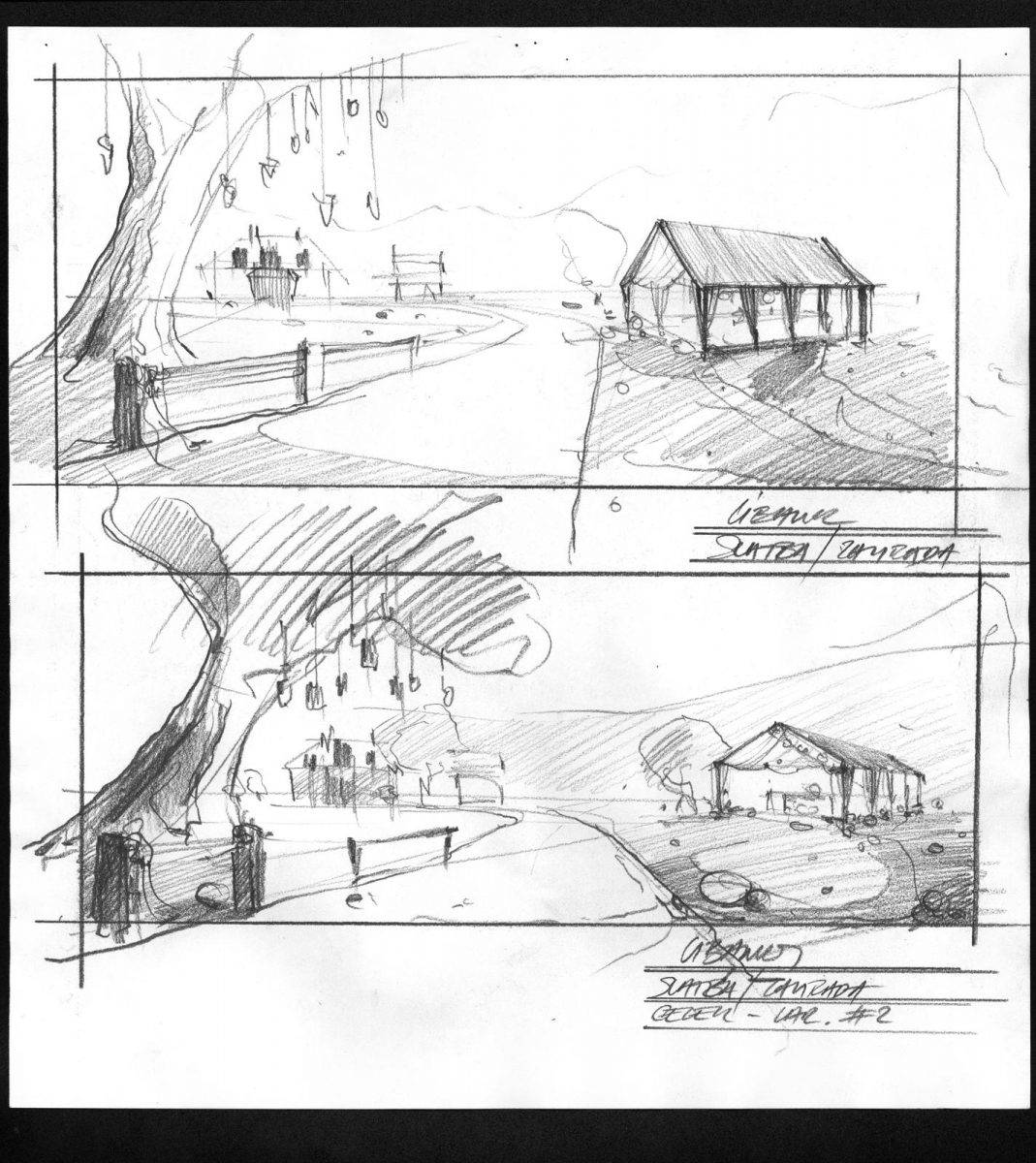

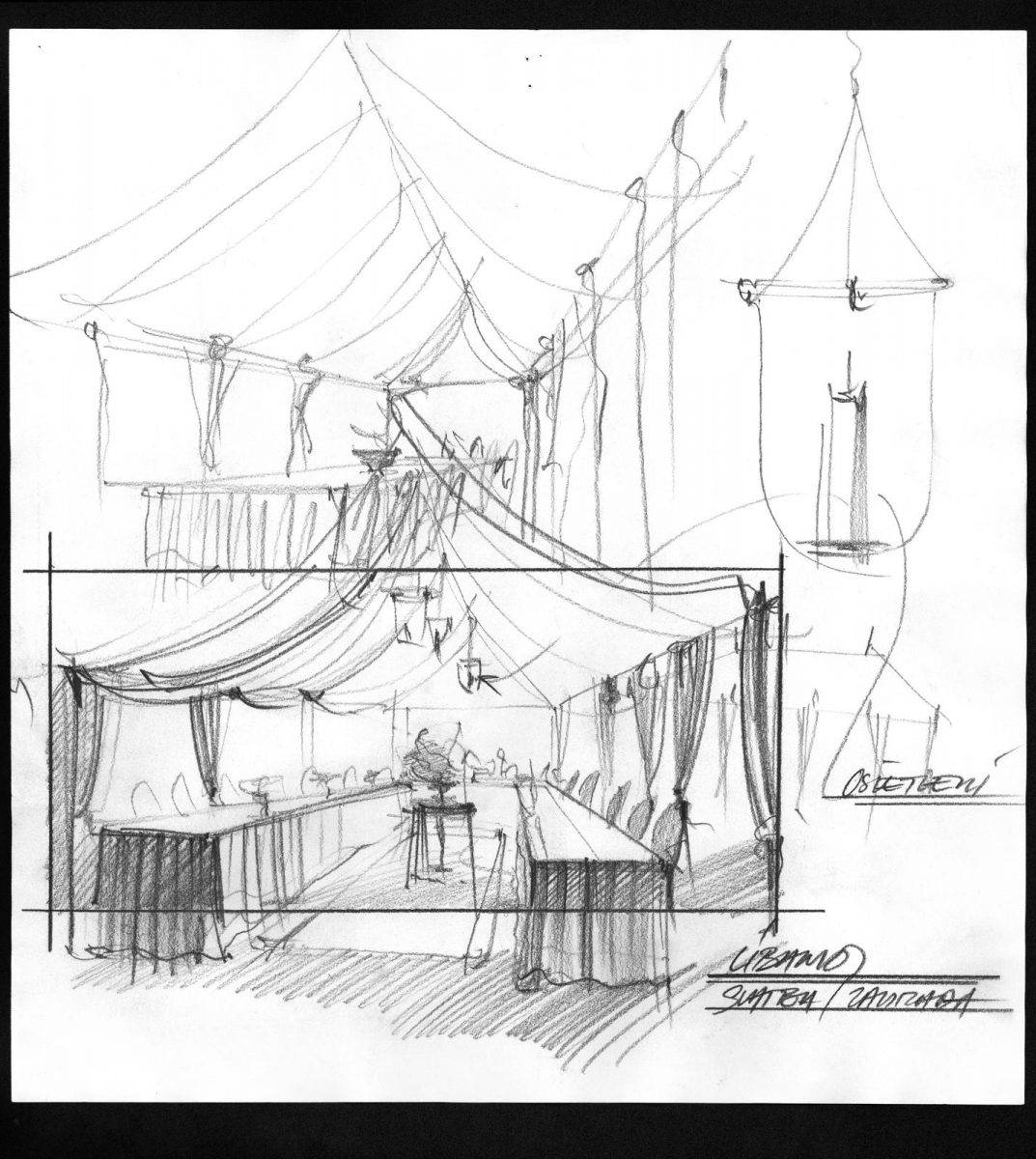

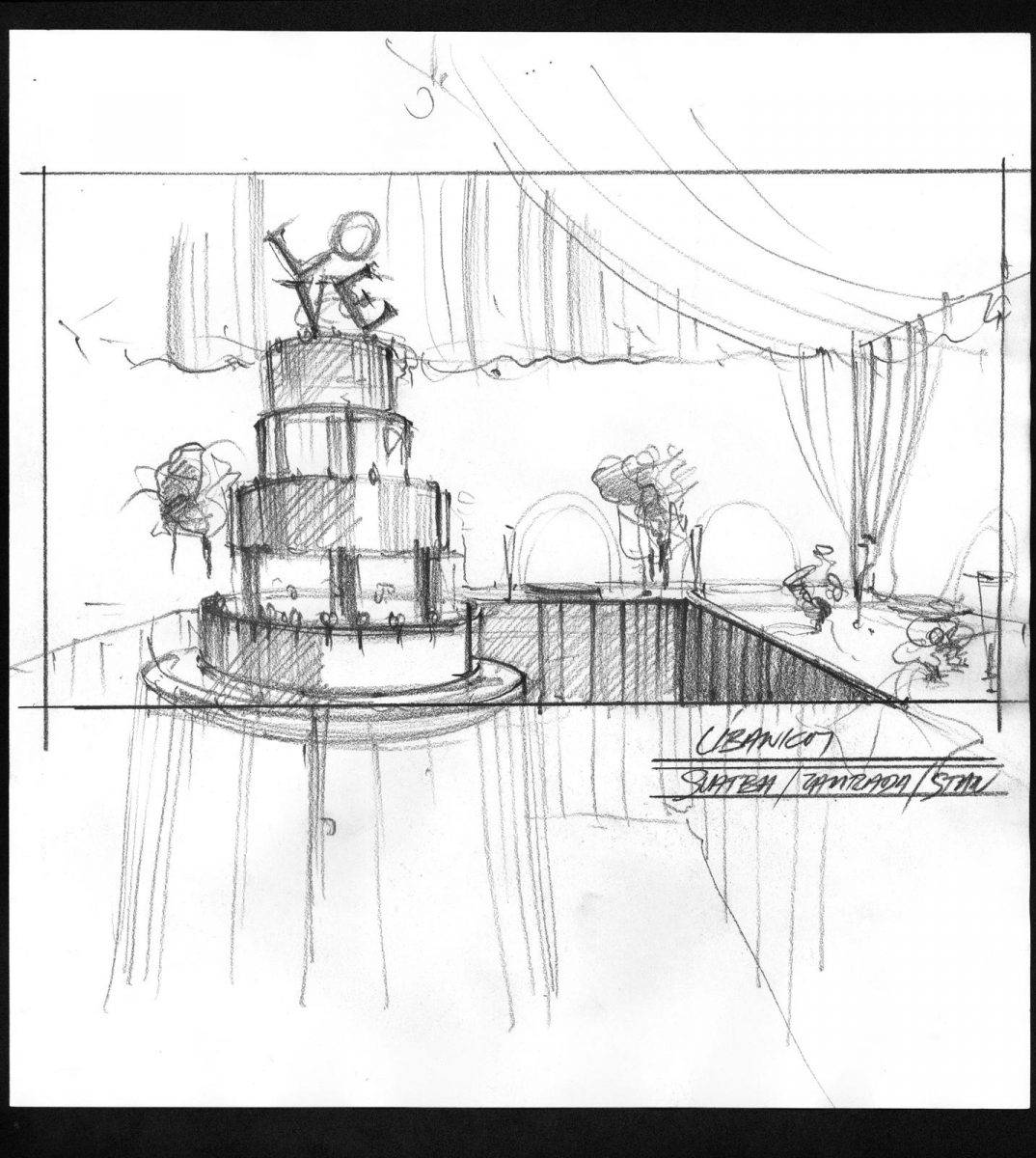

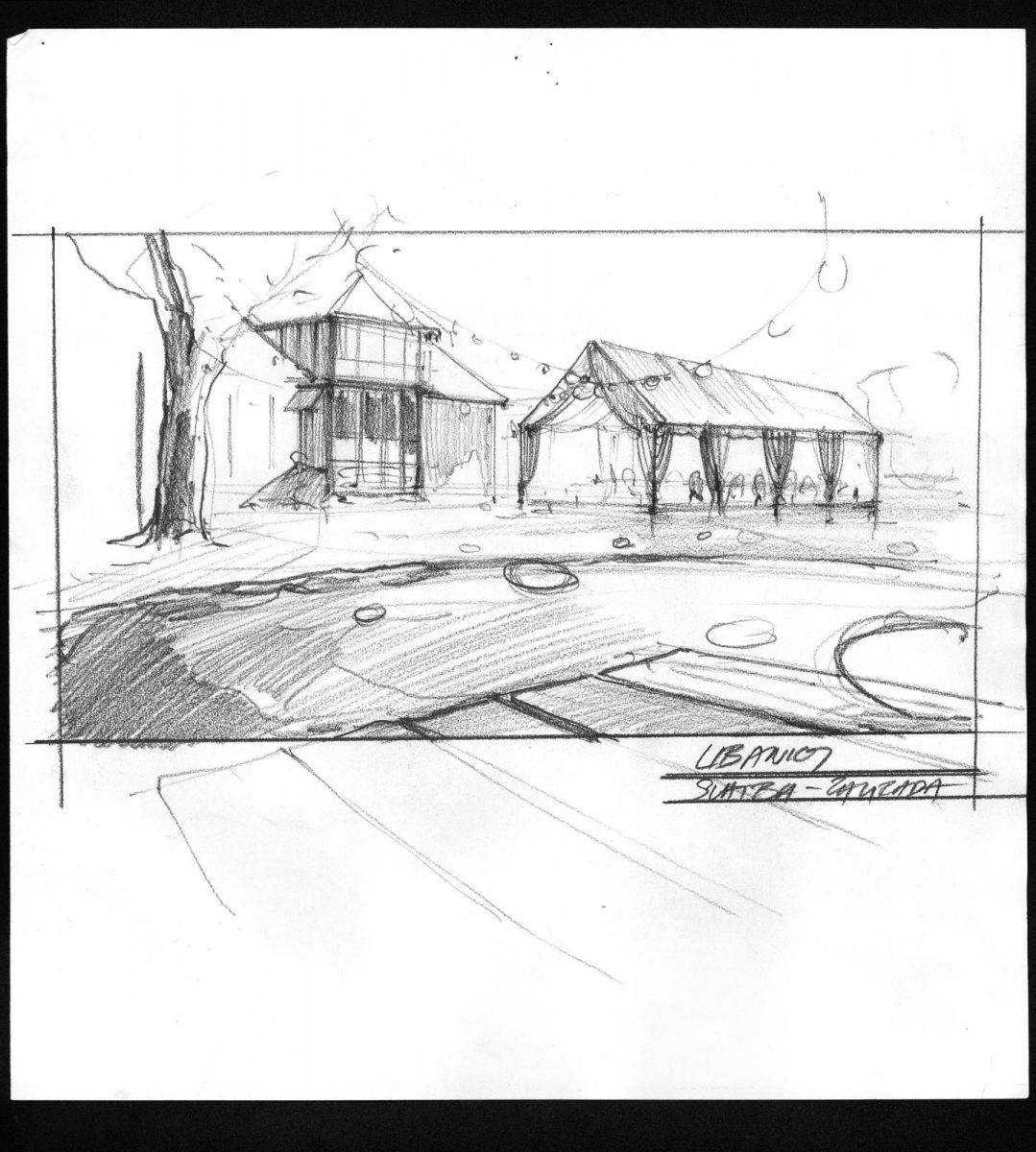

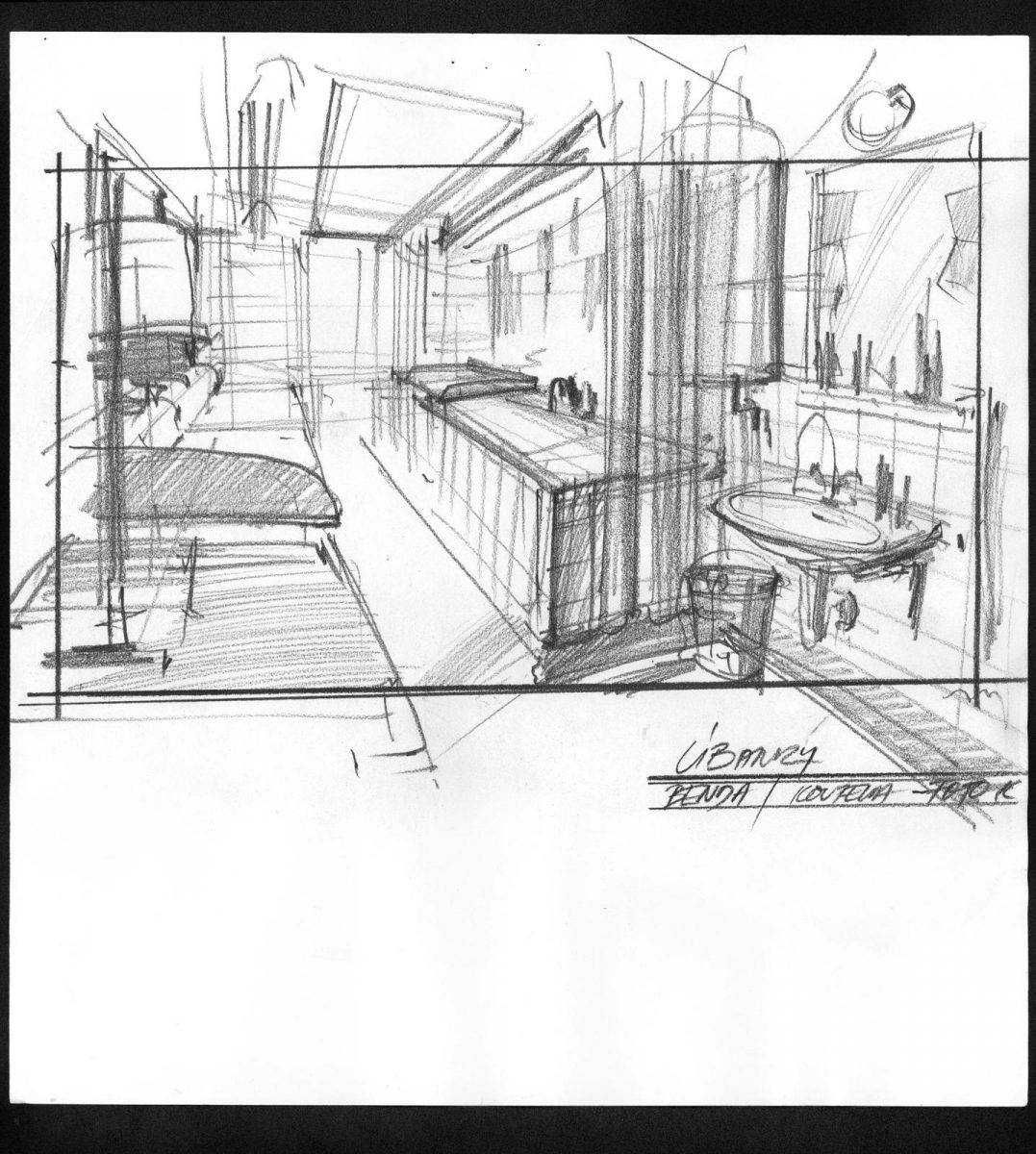

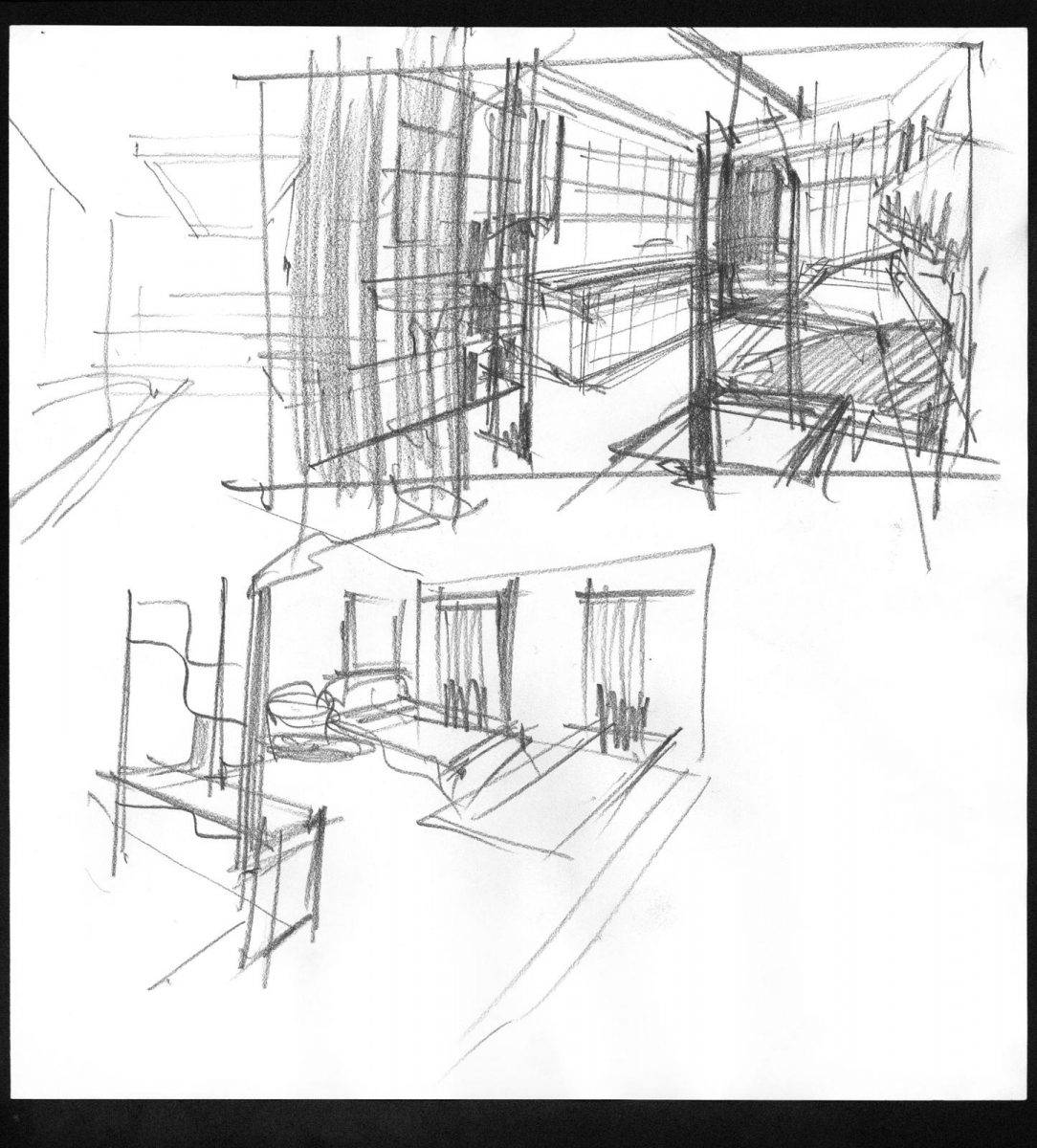

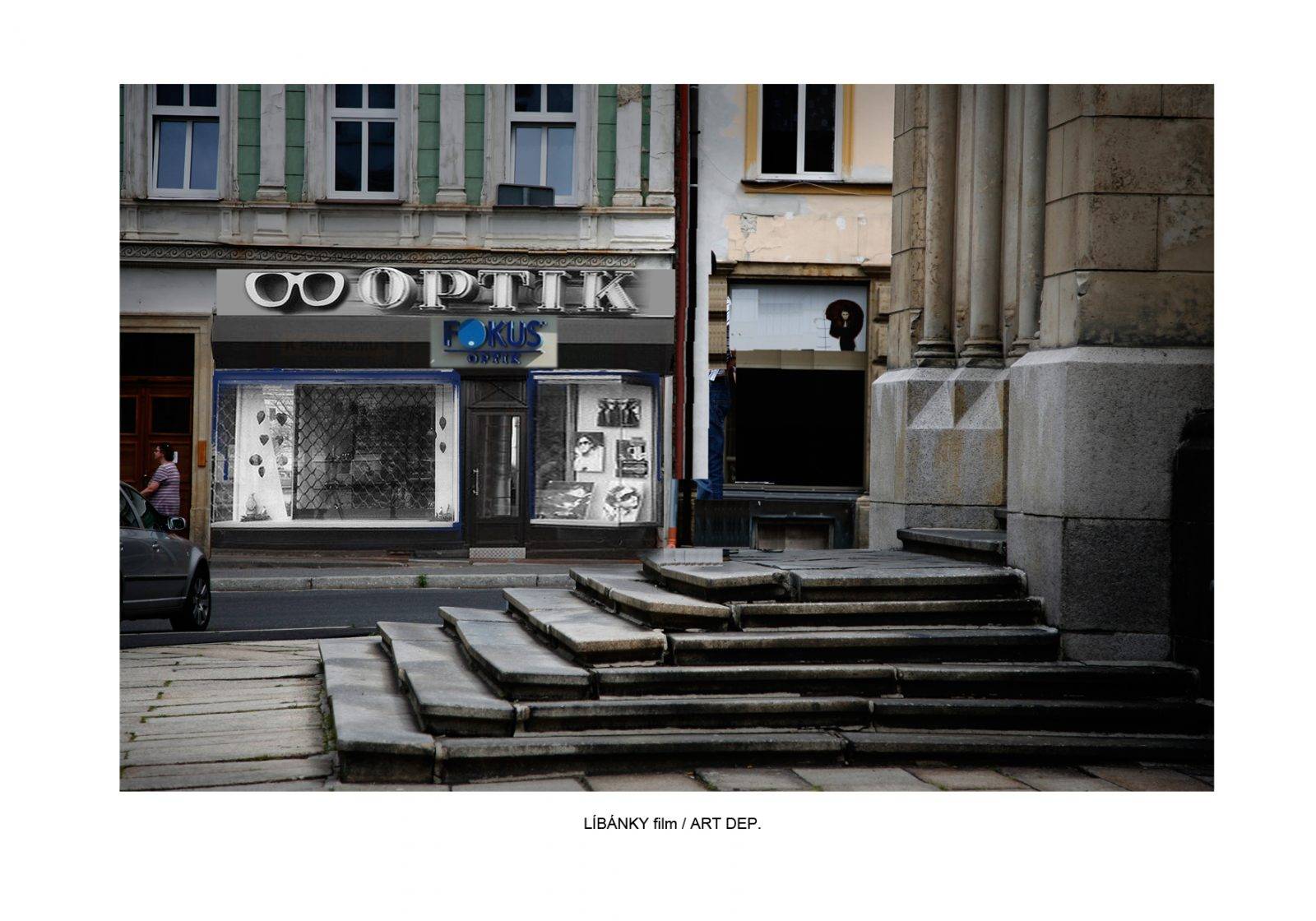

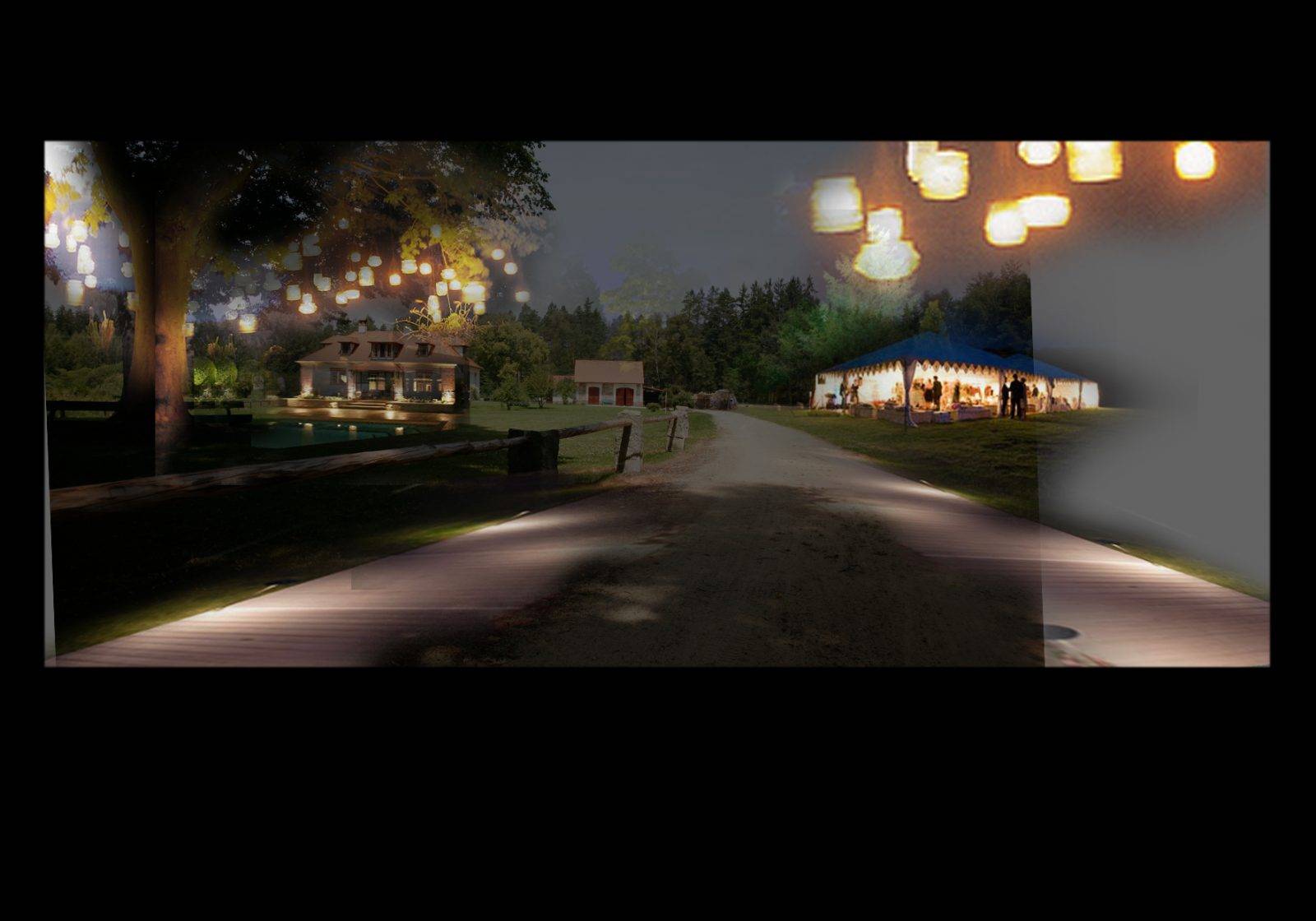

To be honest we never consciously planned any kind of trilogy. We rather attempt to point audiences in the direction of what they should expect… Honeymoon is a distinctive film, an intimate drama which in this case takes place over the course of a single afternoon, the wedding night and part of the next day. It was a challenge for all involved, and in addition I worked with a fundamentally altered team – cameraman Martin Štrba, architect Jan Kadlec, sound engineer Lukáš Moudrý, editor Alois Fišárek. And the producers Viktor Tauš, Mišo Kollár and Tomáš Rotnágl.

In your opinion is it necessary to reveal past secrets, and specifically in the case of Honeymoon, is a forgotten misdemeanour from youth a reason for a person to be confronted and punished for it?

That’s difficult to say – I hope so. This time the film is to a considerable extent our personal testimony. In it we ask various questions which we consider important. In its way the film is an example of how the human conscience works. I’d say that this story is emotionally riveting. Perhaps because it could happen to anyone. It actually concerns an inconspicuous, understandable, almost innocent evil…

Honeymoon is the fourth time you’ve worked with Aňa Geislerová, who is one of the core actresses of your films. What are the advantages or disadvantages of this co-operation, when you know each other so well, on both a professional and personal level?

There’s only one disadvantage: It gets harder and harder not to repeat yourself. The greatest advantage so far has been the fact that we have mutually attempted to excel ourselves. To get into Petr’s characters, to fine tune the co-ordination, take the audience’s breath away… And to do this with subtlety. I hope it works. And I also have the feeling that the others act better with Aňa. This also applies for example to Bolek Polívka. It’s not possible to say about every star that they are a collective, team player…

Was the role of Tereza written specifically for Aňa?

No. We’ve never written a specific role for anybody. With the exception of the adolescent Kšanda (Jan Semotán) in Big Beat.

One of the questions the film asks of the audience is whether, on the basis of a relationship and a given promise, a person should forgive, and what the limits of that forgiveness are. If you yourself had to define the limit beyond which it’s no longer possible to forgive, what would it be?

That depends on the specific individual and his or her inner strength. On circumstances which are different in each case. In this respect our film asks questions, never answers them.

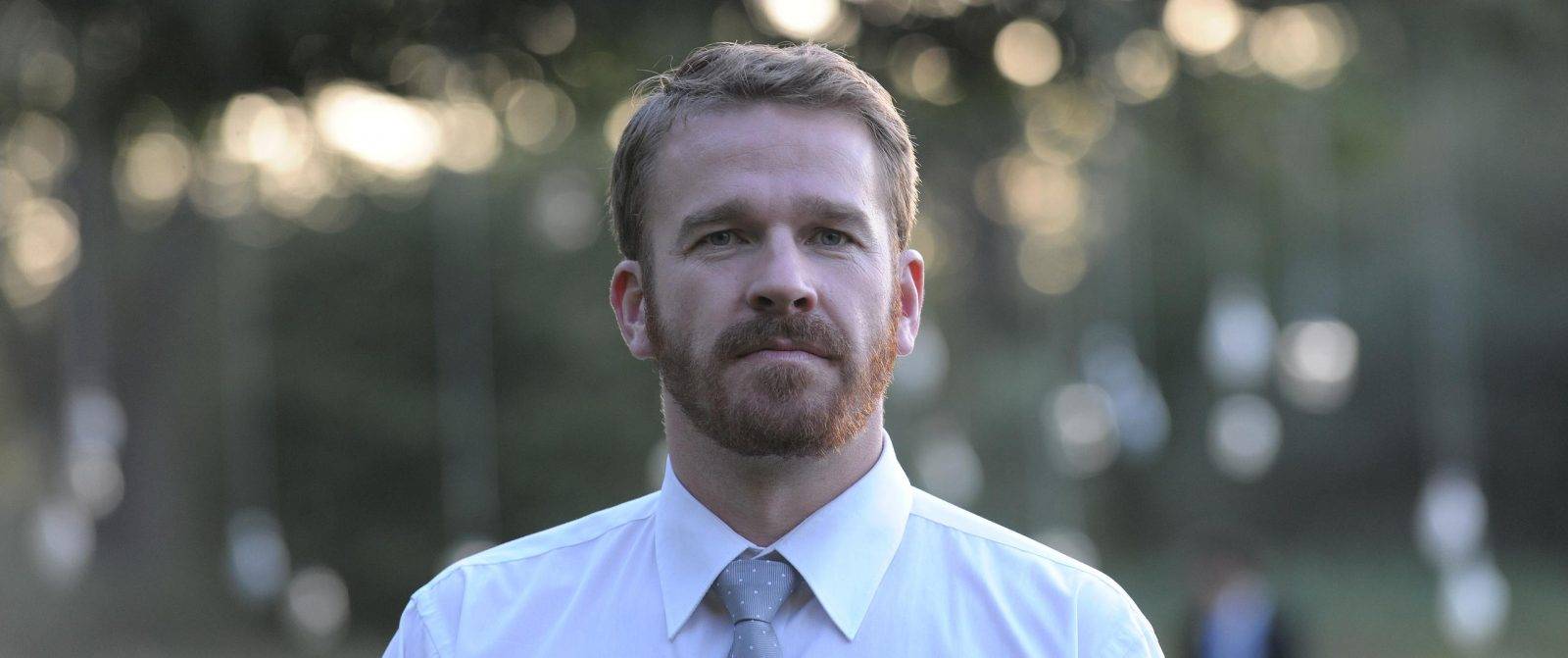

In your films you like to introduce new or lesser known acting talents. Why did you choose Stanislav Majer and Jiří Černý?

Because it’s an immense thing to introduce to the wider public someone you admire – for example in the theatre. Over the course of several years I’ve experienced several overwhelming moments at performances of the Chamber Theatre in the Comedy Theatre, and it all culminated last year with the filming of Garbage, the City and Death… From that we moved directly with Standa and Jirka to Třeboň, where we filmed Honeymoon. The Chamber Theatre was an exceptional pool of literally phenomenal talents – not only acting (Finger, Pechlát, Štrébl, Zach, Uhlířová, Míčová, Kamila Polívková, Ivan Acher…). And a whole range of theatres and cinematography will continue to draw from this pool, that you can bet on!

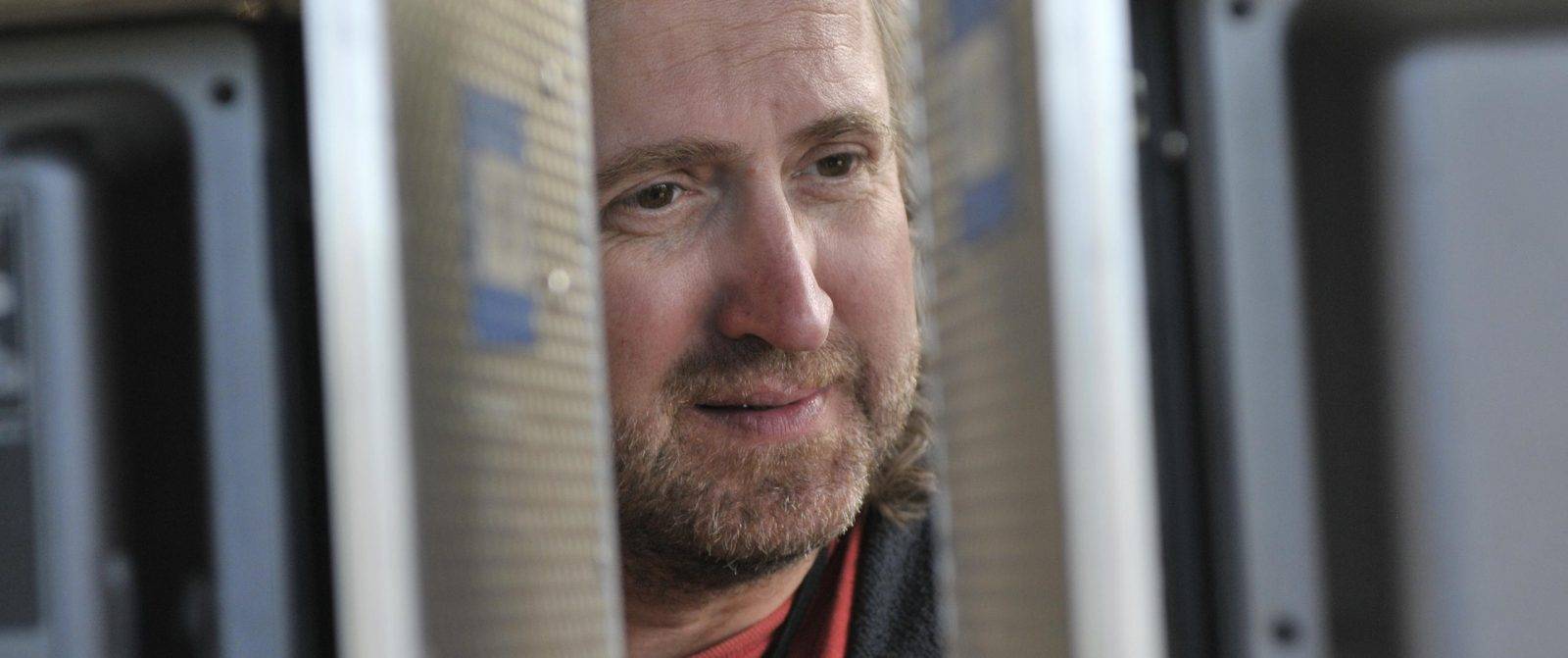

Petr Jarchovský – screenwriter

Honeymoon should thematically conclude the loose trilogy of Kawasaki’s Rose – Innocence – Honeymoon, which as its central theme combines the motif of a secret in the past which can have an unexpected impact upon the present. Do you regard Honeymoon as such a conclusion of this trilogy?

I can’t guarantee that I won’t write another story in future in which the past comes back to haunt the present of the characters and impact upon their lives. The personal history of the characters provides fertile soil for drama. From the beginning we never conceived the films Kawasaki’s Rose, Innocence and Honeymoon as a trilogy. In the end we were captivated by a thematic connection: if we don’t acknowledge our past and admit our own guilt first of all to ourselves, and then to those around us, we’ll never gain absolution and forgiveness.

In your opinion is it necessary to reveal past secrets, and specifically in the case of Honeymoon, is a forgotten misdemeanour from youth a reason for a person to be confronted and punished for it?

As can be seen from the story: if there are victims who have suffered because of our offence, then yes. It’s not about punishment, but acceptance of responsibility. Our stories don’t bring unequivocal judgements. It seems far more beneficial to me to ask questions. The audience can go through their own thought process which our characters are experiencing “on the big screen”. If this happens, then our endeavour hasn’t been in vain.

Jan Hřebejk says that the role of Tereza wasn’t written directly for Aňa Geislerová, nevertheless she has merged perfectly with the character. Do you really have no actors in mind when you’re writing a story, in particularly when it concerns someone like Aňa, who you’ve worked with for many years?

For us Aňa is an exceptional co-creator of female characters. She forms them in the phase of the individual versions of the screenplay, she seeks herself in them, she searches for the key to their motivations, she wants to know and understand them and work out her approach to them. She is without doubt one of the most remarkable actresses, who is able to play the roles of diverse characters, such as in my case Hana in Želary, Marcela in Beauty in Trouble, the mother in National Identity Card, Anna in Teddy Bear or Lída in Innocence. Each character is entirely different in all respects and highly convincing. I regard our meeting, which began when Aňa was only thirteen in our joint artistic debut Let’s Sing the Song Naked-on, to be a huge stroke of luck. As regards the phantom actors I imagine when I’m writing a script, they’re mostly immortal giants or unattainable stars such as Nataša Gollová or Dana Medřická, or perhaps Cate Blanchett, Emma Thompson or Kate Winslet …

The story’s main heroine finds herself in a situation in which, on the basis of her promise, is to remain with her husband “for better or for worse”, and therefore also to forgive. Do you believe in forgiveness, and if you yourself had to define the limit beyond which it’s no longer possible to forgive, what would it be?

I believe in forgiveness. We examine the limit beyond which it’s no longer possible to forgive in our films, and we ask ourselves the question that all of us have to try and answer. It’s important for each of us to do this alone in order to conduct an inner debate with our own conscience.

Whilst in Kawasaki’s Rose for example evil was the personification of a certain social phenomenon, in Honeymoon it concerns rather a “small human” evil, which however is probably no less dangerous. Isn’t it however just a question of possibilities? That the person who has this within himself or herself, manifests evil depending only on the circumstances to which degree?

I wouldn’t dare to divide people into the “bearers of evil” and the “good ones”. (Such clearly defined storylines are the business of fairytales or genre films). In real life, all of us have both sides in ourselves. We are interested in the causes that form us, and the situations which make a certain aspect to come to the surface within a character. This selfsame situation of danger may have entirely opposite effects on two different characters: for example in our film Divided We Fall, the deadly threat in the era of the Nazi occupation generates entirely different reactions and attitudes on the part of the characters. The main hero behaves courageously, whereas the neighbour is perfidious. We’re therefore interested by the given factors, the internal mechanisms of the characters, which predetermine the development and transformation of each character. And through their development we attempt to ask questions to ourselves.

In a dramatic scene with Tereza, Radim defends himself with the assertion that his present self has nothing in common with his past self. Do you believe that people can genuinely change, or is this merely an excuse before their own conscience?

That is the fundamental question which our drama asks: are there limits to how responsible we are for our actions? For this reason we place the moment of Radim’s offence at the threshold of adulthood. The answer to this question must be polemical. Unequivocal judgements have always provoked us, forced us to examine the character from all sides and points of view. We’ve never been interested in apportioning blame, but in getting a true picture of the issue which the genre of psychological drama provides.

Aňa Geislerová – actress

Honeymoon is a film full of questions of which the most important is this: In your view is it necessary to reveal past secrets, and specifically in the case of Honeymoon, is a forgotten misdemeanour from youth a reason for a person to be confronted and punished for it? What would be your answer?

That’s difficult. There are things that people aren’t proud of on emerging from their “adolescence”, and I think all of us have something like that. But they’re generally harmless, awkward or embarrassing things. What happens in the film is not just some childish prank or banter. It’s a dark, malignant offence, committed by people who must have suspected its consequences. This can’t just simply be erased. I’ve taken plenty of knocks in my life, and a few of them have been unnecessarily cruel and confrontational, but I’ve also learnt a few lessons, so it’s all ended up smelling of roses. And I also now know that everything will eventually be revealed anyway. I think it’s important how a person adopts an approach with hindsight. If they understand that they’ve done something wrong, they can apologise, be forgiven, and it can be forgotten. Or they can deny the past, and that’s never a good thing. Wounds need to be cleansed in order to heal.

Jan Hřebejk says that the role of Tereza wasn’t written directly for you, nevertheless this character will undoubtedly be another important moment in your career. How did you feel in this role, and what about her did you most identify with?

I’ll start with what I was absolutely taken with. That’s the fact that for most of the film I’ll be made up, perfectly groomed and well dressed. I’ve been in so many roles without make-up. When we formed the character, we spoke about a woman who has everything perfectly arranged. In her finances, her car, wardrobe, future plans. As a result I can say I have virtually nothing in common with her. The entire filming was wonderful, and it was a great crowd of people in the summer in Třeboň.

The story’s main heroine finds herself in a situation in which, on the basis of her promise, is to remain with her husband “for better or for worse”, and therefore also to forgive. Do you believe in forgiveness, and if you yourself had to define the limit beyond which it’s no longer possible to forgive, what would it be?

It’s not possible to live without forgiveness. You cannot free yourself from a burden and go on with your life. I’m able to forgive, but not forget. And everyone has a different threshold. What some people can overlook, others can never get over. But cold, calculated cruelty, evil intention can never be forgiven. And also people have to be able to forgive themselves.

You’ve worked with the pairing of Hřebejk and Jarchovský for almost your entire acting career, Honeymoon is now the fourth time Jan has directed you. What are the advantages or disadvantages of this co-operation, when you know each other so well, on both a professional and personal level?

In short the advantage is the years we have behind us. But as in every long-term relationship, an advantage can quickly turn into a disadvantage. But the longer I know Jan, the more I admire him, and the same goes for Petr. I think we’re all joined together by the fact that for us it’s a genuine pleasure to go to work.

Was there any characteristic or element of the main character you contributed to either after reading the script or on location, something you either added or took away?

It’s funny, but I thought up the possibility that Tereza could be pregnant. It seemed to me that emotional hysteria and vigilance brought on by pregnancy could be the antithesis of her perfection. The sense of being in danger and exaggeration of everything. And the subsequent paranoia, when a woman sees hormones behind her every judgement. I think that in her case it’s clear that at that moment she is incapable of resolving something so unpleasant rationally. She wants it to just disappear, just go away. For the world to be once again as uncomplicated as she had built it. And now I’m bringing this idea to fruition… An exacting method of acting!

Jiří Černý – actor

After the film Garbage, the City and Death, Honeymoon is the second time you’ve worked with Jan Hřebejk, but the first time on an original film project. How was he to work with, what suits you about his approach, and are there any examples of moments which don’t suit you?

I enjoyed the preparations, we rehearsed, which today is unfortunately no longer the standard. Jan’s sense of humour suits me, though at certain moments it doesn’t suit me.

Through the medium of its characters, the film asks the audience the question of whether a person should bear responsibility and thus also be punished for something committed in the past. How would you respond to this question?

Punishment is just and inevitable. The worst punishment is a guilty conscience.

The main characters of the film resolve within themselves the question of whether it is possible to forgive someone close to them for their offence, and to stay with them “for better or for worse”. Do you believe in the need for forgiveness and is there a limit beyond which it is no longer possible to forgive?

I think everyone has to forgive themselves.

Jan Benda is a highly ambiguous character – on the one hand a victim, on the other, when he unexpectedly gains the opportunity for revenge, he doesn’t hesitate to take it, even at the price of using a person who hasn’t committed anything, namely Tereza, for this purpose. How did you view this character?

He also could have done nothing. In our case, however, he didn’t have the time to consider the legitimacy of his actions, let alone the potential consequences. In addition, who is Jan Benda?

Was any element of the character or any situation created on your initiative or following mutual discussions with the director or your colleagues?

I was most helped by Jan Hřebejk’s humour.

Viktor Tauš – producer

How did your co-operation with the pairing of Hřebejk+Jarchovský on Honeymoon come about?

I was asked to produce the film by Petr Jarchovský during the preparations for our film Clowns. In terms of energy it wasn’t the ideal moment… But I love the films of Jan Hřebejk and Petr Jarchovský, and I just couldn’t say no to the script of Honeymoon. However, it’s necessary to say that we were incredibly lucky, since Czech Television supported us. Without their help it wouldn’t have been possible to record the film within the given time.

What interested you as a producer in the script of Honeymoon, and why did you decide to produce the film?

I think Honeymoon is Petr’s best screenplay since “Divided We Fall”. It’s exceptional for its compactness of space and time within the joint work of Hřebejk and Jarchovský. I looked forward to seeing how Jan could construct a feature length film on the basis of two days of a wedding celebration.

What do you consider the film’s greatest strength?

The superb acting performances and also the striking, very elegant visuality of the film.